I was excited to have the opportunity to be one of the three presenters on a webinar on 28 July 2017, exploring inclusion and compassion from a leadership perspective in the NHS. Here are the slides with my notes from the presentation…

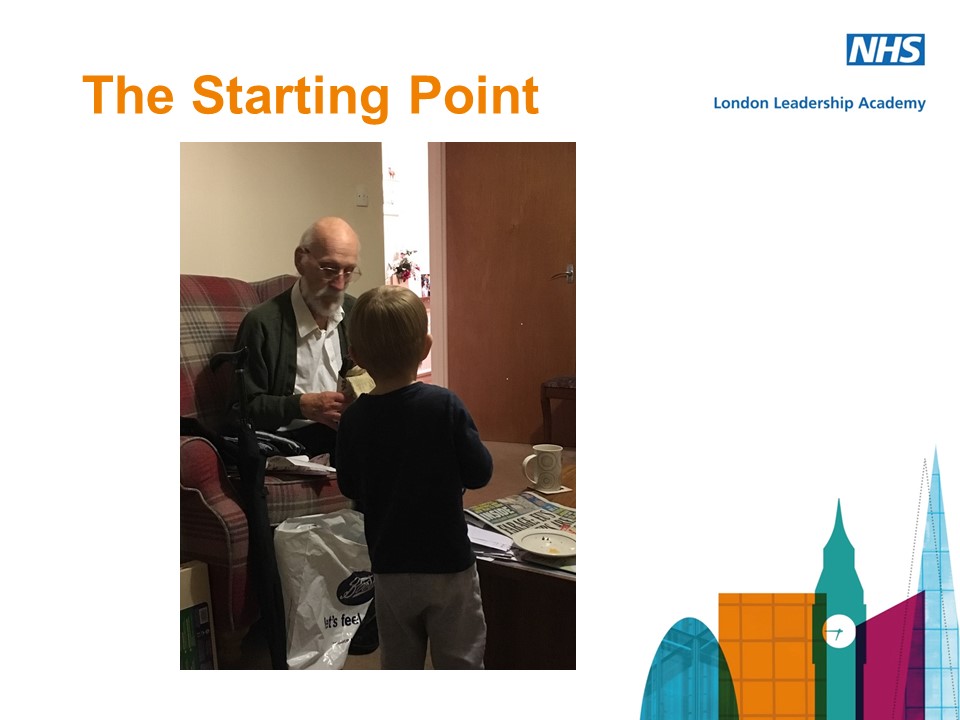

This is my 90yo father, whose name is John, with my three year old son, called Thomas.

Any thoughts that I might have about health and social care tend to pivot around the experiences of these two. Whether I am considering how care wraps around the client or how education might support the delivery of powerful messages around health promotion, Dad and Thomas help me to focus on the truly human dimensions of these vital – but oftentimes abstract – considerations.

From the core issue of how the systems that exist around these two can be made to work effectively for them both through to how they each might experience care when they need it in reality, whether from a home care company or a GP practice, this orientation is vital in order to ground those deliberations.

Notwithstanding my opinions as to the effectiveness of care and the quality of the experience for Dad and Thomas, there is a post-Francis recognition of the need to redirect our systems, organizations, teams and individuals to the keystone of good health and human services, namely compassion. This recently published document makes a strong and persuasive case for the importance of improvement and leadership as key facilitators in the delivery of better care.

Condition 2 in this document stipulates that there should be

Compassionate, inclusive and effective leaders at all levels

By which it means that,

‘Compassionate leadership means paying close attention to all staff; really understanding the situations they face; responding empathetically; and taking thoughtful and appropriate action to help.

‘Inclusive leadership means progressing equality, valuing diversity and challenging existing power imbalances. It may sound a ‘soft’ and timeless leadership approach given current urgent pressures. But evidence from high performing health systems

show that compassionate, inclusive leadership behaviours plus established improvement methods create cultures where people deliver fast and lasting improvement in quality and efficiency.’

West et al (2017) suggest that ‘Compassionate leadership enhances the intrinsic motivation of NHS staff and reinforces their fundamental altruism.’

I’m going to look at the intimate relationship between these three elements; in particular, the idea that, for compassion to flourish amongst people who work alongside each other (and thence to the people for whom they are offering care), leadership practice needs to engender self-compassion as a way of being for our people and to create an organizational climate that is, in itself, compassionate and thereby supportive of compassion.

Towards the end of the session, I highlight some practical actions – from my experience working in a mental health trust in London and on the basis of my time at the London Leadership Academy – that help us to understand what compassionate leadership might look like.

I could’ve chosen any site, of course, but this is Northwick Park, a large acute care provider in London. I wanted to use this image to begin by underscoring how and where we tend to deliver care in the NHS. Michel Foucault spoke, in The Birth of the Clinic, of a move away from a domestic setting to a clinical one in medicine, from the bedside in the home to an environment created specifically as somewhere for care to be delivered.

One issue with this is the way in which such places tend to be industrial in terms of scale and process – and I’m using Charles Sheeler’s 1930 painting entitled “American Landscape”, which is a rendering of the Ford Motor Company plant on the River Rouge near Detroit, Michigan, to underscore a visual similarity between a large hospital and a production site.

In such a context, it can be argued that people become objects of care rather than subjects navigating their way through illness and wellness. Both settings are examples of form following function – and both are built around process. In such a context, it becomes a specific challenge to all to hold onto the idea of compassion as a core element of their practice.

So, what can we usefully say about compassion, with this idea in mind?

The very notion of compassion is far from straightforward and can be seen to have a challenging provenance. Karen Armstrong, a noted author on this topic, states in her Charter for Compassion that,

‘The principle of compassion lies at the heart of all religious, ethical and spiritual traditions, calling us always to treat all others as we wish to be treated ourselves. Compassion impels us to work tirelessly to alleviate the suffering of our fellow creatures, to dethrone ourselves from the centre of our world and put another there, and to honour the inviolable sanctity of every single human being, treating everybody, without exception, with absolute justice, equity and respect.’

Importantly, the idea of compassion extends beyond merely feeling sympathy; it commands action to address the suffering of others, wherever that manifests itself. Moreover, its relationship with religious and spiritual practice can problematize it in the rationalized and diverse practice sphere of health care. It is perhaps for this reason that notions such as “intelligent kindness” have arisen, defined in the following way:

‘Kindness implies the recognition of being of the same nature as others, being of a kind, in kinship. It implies that people are motivated by that recognition to cooperate, to treat others as members of the family, to be generous and thoughtful. The word can be understood at an individual and at a collective level, and from an emotional, cognitive, even political point of view. Adding the adjective “intelligent” signals, first, that it is possible to think in a sophisticated way about the conditions for kindness and, second that clinical, managerial, leadership and organisational skills and systems can be brought to bear purposively to promote compassionate care.’

[Campling P (2015) Reforming the culture of healthcare: The case for intelligent kindness. BJPsych Bulletin. 39. 1-5]

This, then, speaks strongly of how we relate to one another – and has implications in terms of diversity, inclusion and engagement.

There is a strong argument to suggest that compassion cannot simply be an externally facing attribute of human existence: an acknowledgement of suffering, a connection with it, and the development of a will to alleviate it should apply both in terms of our relations with others and in respect to our reflective selves. It is argued that this self-compassion has three components: self-kindness; common humanity; and mindfulness, specifically being aware of one’s thoughts and pain but not overwhelmed by them.

[Neff K (2003) Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude to oneself. Self and Identity. 2. 85-101]

If a leader is expected to be an exemplary figure, then they should be showing self-compassion – as well as compassion to those with whom they work. An HBR blog recently cited research that had found that the more employees look up to their leaders and are moved by their compassion or kindness (a state termed elevation), the more loyal they become to him or her. So if you are more compassionate to your employee, not only will they be more loyal to you, but anyone else who has witnessed your behaviour may also experience elevation and feel more devoted to you.

The article suggested that leaders, when facing employee mistakes, should avoid reprimanding and instead: take a moment; put yourself in their shoes; and find the power to forgive.

The second key element to this is engendering a climate of organizational compassion, which speaks to how people interrelate in the workforce – how thoughtful they are about the suffering of those with whom they work and how they respond to that – as well as how well leaders create a workplace that is inclusive, engaged and supportive to all who work there.

In this space can be found the ideas of value-based leadership, a practice that gives reality to compassion in an organizational context by demanding of leaders that they work with an underlying but explicit moral, ethical foundation [Copeland M K (2014) The emerging significance of values based leadership: A literature review. International Journal of Leadership Studies. 8:2. 105-135.]

In the health context, it expects leaders to act as a connection between the organizational values and those of the workforce, which may have become detached in light of the expectations of the work context.

Increasingly, however, we expressly reference compassionate leadership. A recent Kings Fund publication on this topic made an express connection between this type of leadership and innovation, not least because ‘Compassionate leadership is inclusive in ensuring that the voices of all are heard in the process of delivering and improving care’ – and where space is offered without judgement or imposition for staff to experiment around doing things differently and better [West M et al (2017) Caring to change: How compassionate leadership can stimulate innovation in health care. London: Kings Fund.]

Importantly, as well, compassion may be under pressure in the workplace when, as recent research by Roffey Park suggests, ‘…the pressure for performance, productivity and efficiency […] reduces the capacity of employees to notice another person’s suffering.’ [Poorkavoos M (2016) Compassionate leadership: What is it and why do organisations need more of it? Horsham: Roffey Park Institute.]

It’s vital to acknowledge that compassion in leadership is not a bolt-on, sitting alongside all the other facets that are seen to be intrinsic to solid and effective practice in this area. It forms part of the wider picture of leadership in the contemporary health and social care context, where transformation, integration, systems thinking, wicked problems, innovation, inclusion and engagement are all in play, when one is considering how to enhance effectiveness and support improvement.

So, I want to finish with a few practical things have I been engaged in that contributed to this, over the past couple of years.

At Camden & Islington NHS Foundation Trust, we piloted a revised approach to performance appraisal, which asked managers to meet their direct reports for an hour on a quarterly basis. It asked those managers to think about their whole team, rather than simply the individuals (and their defined job roles within it), and asked managers to look back and look forward on a ninety day basis, rather than a full year.

Managers were supported in respect to running these conversations from a coaching perspective, with the emphasis being on the team’s challenges over the coming three months and the staff members contribution to helping the collective to meet those expectations. To that extent, managers were introduced to the GROW model and the important notion of situational leadership.

The success of the pilot has seen this model rolled out across the whole trust this year, with some adjustments. Importantly, it presages a climatological shift in the organization as part of a wider commitment to move from a directive to a supportive management style across the whole trust. Importantly, it connects with the vital notion of offering positive feedback, something which can oftentimes be unjustifiably in desperately short supply in the health and social care context.

At the London Leadership Academy, we are offering a five day programme spread across three months to allow leaders to consider their practice through the lens of compassion. An immersive and profoundly reflective experience, the first cohort has offered very positive feedback on the course, delivered for us by Katy Steward and Byron Lee, although we are keen to explore with participants the extent to which they have been able to lead differently in respect to their oftentimes difficult circumstances. The second cohort of this programme will launch in September and we already have a great deal of interest in it.

Our flagship work in this respect related to the vital issue of speaking truth to power – and, in particular, to ensuring that individuals, particularly senior leaders, offer a space where a polyphony of voices, representing diverse opinion and experience, can be heard to be freely filling the organizational space. Working with Ben Fuchs and John Higgins, we offer a full day for people to explore notions of speaking up and listening up – and, more recently, have provided participants with the opportunity to encourage their team, department, trust or system to undertake an anonymized survey on this issue – and to then have a facilitated conversation off the back of the report generated by this.

The LLA and our collaborators are continuing to explore and enrich this offer: we are committed to work to bring the issue of trust into sharp relief in regard to this…and similarly are keen to help organizations to explore, understand and adjust the quality of their meetings, in order that there is a truly compassionate and inclusive approach to hearing the voices from across the workforce.

All of the above serves to reestablish the individual at the centre of any leadership practice, to take a humanistic view of the business of managing busy and complex services at a time of great change. Leadership is a constant in regard to overseeing the delivery of goods and services: it is the context that changes, insofar as we are aware that the best outcomes in this regard will derive from practising leadership in a compassionate and inclusive way, from the perspective of systems challenges.